Sig Engineering - Part 8 - Sig’s SVM and Runtime

We're excited to announce that we have finished implementing Sig validator’s SVM and runtime. This post will explain what the runtime is, why it matters, and how ours works.

We're excited to announce that we have finished implementing Sig validator’s SVM and runtime. This post will explain what the runtime is, why it matters, and how ours works. This post is Part 8 of a blog series we periodically release to share Sig's engineering updates. You can find other Sig engineering articles here.

Every Solana validator has the same simple-sounding job: executing transactions and updating accounts. But the software that actually does this work—the runtime—is anything but simple. Every transfer, vote, DeFi trade, and NFT mint is executed by this one component. It must emulate a Turing-complete computer and reproduce Agave’s outputs perfectly. There is no formal specification for Solana. Correctness is defined as “this is how Agave does it.” Even a tiny deviation can break consensus. Building a Solana runtime means reverse-engineering thousands of implementation details, validating them with extensive fuzzing and conformance tests, and carefully weighing the trade-off between design clarity and perfect conformance.

If it's so hard, why build another one? Because Solana needs client diversity to stay alive. With only two runtimes (Agave and Firedancer), a bug in either could take down the network by preventing supermajority consensus. A third implementation ensures liveness even if one fails. Sig eliminates that single point of failure and strengthens Solana’s fault tolerance.

We didn’t just rewrite Agave in Zig. We built a runtime with a structure that's easier to understand, with simple and well-defined boundaries between each component. We made concurrency obvious, separated state from execution, and made account access explicit instead of emergent. Along the way, we ended up with a faster sBPF interpreter.

This post will walk through the runtime from the outside in. We’ll start with replay because that’s the runtime’s primary caller—it feeds the runtime with blocks from the ledger. Within the runtime, we’ll start with the block processor, where parallelization occurs, and the transaction processor, where so many Solana-specific details must be handled correctly. Finally, we’ll describe the instruction processor and the low-level details of the sBPF virtual machine, where Solana programs are executed.

This diagram illustrates the architecture of a Solana validator, divided into three layers: networking, storage, and the core validator. Replay and block production are the drivers of the core validator logic, using the runtime to execute blocks and consensus to vote on them.

Replay

Replay is the main loop of a Solana validator that drives the runtime to verify blocks. It connects every major subsystem of a Solana validator: the ledger, runtime, AccountsDB, and consensus. Its job is to continuously pull in new blocks, execute them, and report the results.

Replay constantly cycles through a sequence of steps:

- Scan the ledger for transactions received from the leader.

- Load the accounts required by those transactions from AccountsDB.

- Execute the transactions using the runtime's block processor.

- Commit the updated accounts back to AccountsDB.

- Report the block result to consensus, which decides whether to vote on the block.

Because Solana leaders stream transactions in real-time while they're still producing the block, validators don't need to receive the entire block before starting to execute it. Replay exploits this by operating on transactions instead of blocks: as soon as it detects new transactions, execution begins immediately. This minimizes latency, reducing block times and keeping validators tightly synchronized with each other.

Sig also supports concurrent slot execution. Multiple forks can advance simultaneously, with each replay task maintaining its own execution context. This parallelism allows Sig to maximize hardware utilization without compromising the correctness of execution order.

Runtime

The runtime is the engine that is responsible for executing blocks. It takes transactions and accounts as its input, and produces newly updated accounts as its output.

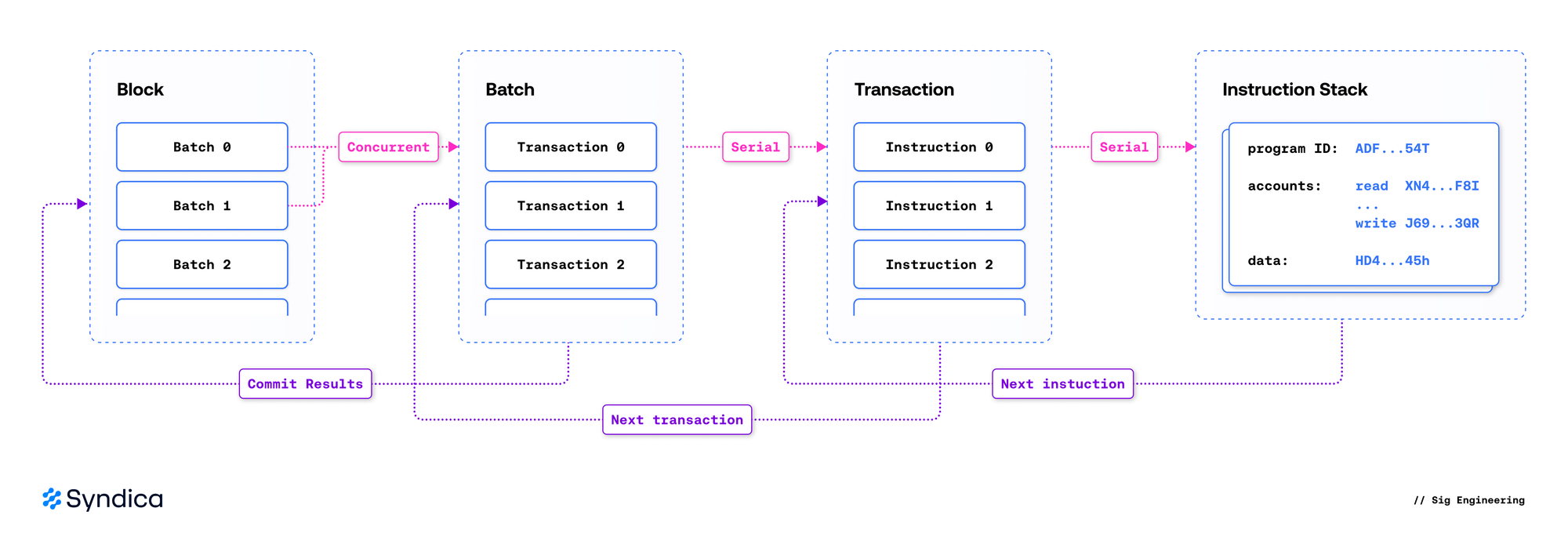

The runtime's structure mirrors the structure of Solana's ledger: blocks contain transactions, which contain instructions. It can be broadly divided into three layers based on the scope in which they operate:

- Block Processor: Orchestrates block execution, manages parallelization by scheduling transactions onto separate threads, enforces account locks, invokes the Transaction Processor, commits the results, and freezes the slot.

- Transaction Processor: Validates a transaction, loads its accounts, runs each instruction in the Instruction Processor, and outputs the transaction’s effects.

- Instruction Processor: Invokes native programs or interprets sBPF bytecode to execute onchain programs.

Block Processor

The block processor is the entry point to the runtime. Replay feeds in a sequence of transactions from a block, and the block processor outputs the results of executing those transactions. The block processor is invoked through the function replaySlotAsync, which initiates the following sequence of events:

- Verify the Proof-of-History hashes are valid for the block.

- Planning

- Resolve the accounts needed for a transaction.

- Schedule transactions for safe and efficient parallel execution.

- Execution

- Execute transactions concurrently in a thread pool.

- Commit the state changes generated by those transactions.

- Freeze the slot after the block is complete, and produce a hash of its state.

Planning

In the planning stage, the block processor examines the transactions from the block and determines when and how they should be executed based on the accounts they will use.

Theory: Account Locks

Solana’s runtime stands out from legacy blockchains like Ethereum because it was designed from the ground up to maximize performance using parallel execution. Most blockchains execute only a single transaction at a time, as their transactions are granted access to the entire state space. If two transactions attempt to use the same account simultaneously, they can interfere with each other and corrupt the data in that account.

Solana takes a more careful approach, with every transaction specifying ahead of time what data it needs. This allows the runtime to execute any number of transactions simultaneously, making Solana incredibly scalable.

To do this, every transaction lists which accounts it will read and which accounts it will modify. The runtime employs a simple yet effective account locking rule: if any transaction modifies an account, no other transaction that reads or modifies that account is allowed to execute concurrently. This is a read-write lock, and it ensures that data races do not occur.

- Writes are exclusive—no other read or write may occur at the same time.

- Reads are shared—they may overlap with each other, but not with a write.

Implementation: Resolve Account Addresses

To plan block execution, the runtime first needs to determine which accounts will be used by the transactions. Many of the accounts are listed directly in the transactions themselves, making this process easy. However, in some cases, transactions specify address lookup tables, which are onchain accounts that contain lists of other accounts that the transaction will use. This requires a multi-step process to identify which accounts will be used by a transaction.

A transaction Message is structured with six fields:

pub const Message = struct {

signature_count: u8,

readonly_unsigned_count: u8,

account_keys: []const Pubkey,

recent_blockhash: Hash,

instructions: []const Instruction,

address_lookups: []const AddressLookup = &.{},

};

The account_keys field is the list of accounts that are immediately known to be needed for the transaction. The address_lookups field specifies the additional accounts that are required for the transaction but must be looked up to be identified.

pub const AddressLookup = struct {

/// Address of the lookup table

table_address: Pubkey,

/// List of indexes used to load writable account ids

writable_indexes: []const u8,

/// List of indexes used to load readonly account ids

readonly_indexes: []const u8,

};

The AddressLookup data type (found in the transaction) indicates which address corresponds to the list of other addresses. The indexes are integers that specify which items from that list are required to execute the transaction.

To get an exhaustive list of accounts needed for a transaction, the runtime uses the resolveTransaction function to look them up with the following steps:

- Look up the address lookup table’s

table_addressin AccountsDB.

If a valid lookup table cannot be found, the transaction is not valid. It is illegal to include this transaction in a block. This will halt execution of the block. A proposed block with this failure must be rejected. - Parse the account as a list of addresses.

- Go through the list, and pull out each of the addresses that are pointed to by

writable_indexesandreadonly_indexesin theAddressLookupstruct. - Repeat this process for every address lookup specified in the message.

- A new list of account addresses is created for the full list of all accounts required by the transaction, including both the

account_keysfrom the transaction message and all the additional addresses we just found in AccountsDB.

Implementation: Schedule Transactions

Now that we know which accounts each transaction uses, the runtime has enough information to safely schedule them for concurrent execution.

The TransactionScheduler assigns transactions to run in parallel on worker threads. It first examines the full list of transactions from a block to determine their dependency relationships. A transaction depends on another if it may not execute until after the other has finished. These relationships form a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

If transaction T1 appears earlier in the block than transaction T2, and they don’t share any accounts, the account-locking rule allows them to run in parallel—there is no dependency. But if either transaction writes to an account used by the other, they may not execute concurrently. Since T1 appears earlier in the block, T2 depends on T1.

if (writable) {

// if we write, we depend on last writer, or the readers who depend on it.

if (lock.readers.items.len > 0) {

for (lock.readers.items) |reader_id|

try txn_deps.put(allocator, reader_id, {});

lock.readers.clearRetainingCapacity();

} else if (lock.last_writer) |writer_id| {

try txn_deps.put(allocator, writer_id, {});

}

// We also become the writer for others later.

lock.last_writer = id;

} else {

// if we read, we depend on last writer & becomes readers for next writer

try lock.readers.append(allocator, id);

if (lock.last_writer) |writer_id| {

try txn_deps.put(allocator, writer_id, {});

}

}Execution begins by immediately queuing every transaction with no dependencies (T1 in our example). When T1 finishes, the scheduler follows its outgoing edge in the DAG to its dependent T2 and decrements T2’s dependency count. Once a transaction’s dependency count is zero, the scheduler queues it for execution. This continues until every transaction has been executed.

// Try to schedule the other workers waiting for us

for (self.waiters.items) |id| {

const waiter = &self.scheduler.workers.items[id];

if (waiter.ref_count.fetchSub(1, .acq_rel) - 1 == 0) {

task_batch.push(.from(&waiter.task));

}

}This approach is optimal because it maximizes parallelism: the scheduler always keeps as many transactions running as the account-locking rule permits.

Execution

Once transactions are scheduled to a thread, that thread runs replayBatch to process its assigned transactions. This function delegates to the transaction processor by passing each transaction and the accounts into executeTransaction, which outputs the result of executing the transaction.

Each transaction will have one of three results: success, failure, or failed validation. If it fails validation, the block itself is not valid, so the execution of the block must be halted and reported as a failure. Otherwise, the transaction result is committed using the Committer, which saves the results into the SlotState.

After executing all the transactions in a block, the slot is frozen with freezeSlot. This involves performing some end-of-block state changes, such as distributing transaction fees to the leader. We then calculate a combined hash of all accounts in AccountsDB along with the block’s metadata. This is the slot hash (sometimes called the bank hash in Agave). Each validator is expected to calculate the same hash for that slot; otherwise, they must have executed a different block. Consensus will verify consistent slot hashes to determine whether to vote on the block.

Architecture

Code readability is one of our primary goals for Sig. To achieve this, our block processor's design has been guided by these principles:

- Make dependencies explicit and clear.

- Surface critical operations at a high level as a clear sequence of steps.

To make dependencies explicit and clear, each section of code requests only the inputs it actually needs, rather than depending on catch-all structures or global state. We avoid hiding heavyweight dependencies behind abstractions and instead pass them directly as high-level parameters. This makes it clear to the reader what drives a component and even lets them anticipate its behavior without reading the implementation. A concrete example is ReplaySlotParams, which defines the exact set of dependencies the block processor needs. Instead of implicitly accessing global state throughout the entire codebase, we define a single function, prepareSlot, whose sole job is to gather those dependencies.

/// Inputs required to replay a single slot.

pub const ReplaySlotParams = struct {

entries: []const Entry,

batches: []const ResolvedBatch,

last_entry: Hash,

svm_gateway: SvmGateway,

committer: Committer,

verify_ticks_params: VerifyTicksParams,

account_store: AccountStore,

};

To surface critical operations at a high level, we identified the steps needed to execute a block and listed them out one by one:

- Verify the ticks within a block are valid.

- Validate the Proof-of-History chain.

- Replay the transactions in a batch.

// 1. Verify the ticks within a block are valid.

if (verifyTicks(logger, params.entries, params.verify_ticks_params)) |block_error| {

return .{ .invalid_block = block_error };

}

// 2. Validate the PoH chain

if (!try verifyPoh(params.entries, allocator, params.last_entry, .{})) {

return .{ .invalid_block = .InvalidEntryHash };

}

// 3. Replay the transactions in a batch

var svm_gateway = params.svm_gateway;

for (params.batches) |batch| {

var exit = Atomic(bool).init(false);

switch (try replayBatch(

allocator,

&svm_gateway,

params.committer,

batch.transactions,

&exit,

)) {

.success => {},

.failure => |err| return .{ .invalid_transaction = err },

.exit => unreachable,

}

}

Likewise, replaying a transaction batch is also described with a clear sequence of steps in replayBatch:

- Pre-process each transaction to verify the signature and compute budget.

- Execute each transaction with the Transaction Processor.

- Commit the transaction results with the Committer.

// 1. Pre-process each transaction to verify the signature and compute budget.

const hash, const compute_budget_details =

switch (preprocessTransaction(transaction.transaction, .run_sig_verify)) {

.ok => |res| res,

.err => |err| return .{ .failure = err },

};

const runtime_transaction = transaction.toRuntimeTransaction(hash, compute_budget_details);

// 2. Execute each transaction with the Transaction Processor.

switch (try executeTransaction(allocator, svm_gateway, &runtime_transaction)) {

.ok => |result| {

results[i] = .{ hash, result };

populated_count += 1;

},

.err => |err| return .{ .failure = err },

}

// 3. Commit the transaction results with the Committer.

try committer.commitTransactions(

allocator,

svm_gateway.params.slot,

transactions,

results,

);Architecture Case Study: Resolving Lookup Tables

Since Solana lacks a formal specification, we derived Sig’s requirements by tracing Agave’s implementation. In Agave, a transaction batch progresses from replay to signature verification to scheduling without an explicit lookup-table step. We noted, however, that transaction batches are converted into five different data structures five times during this process. This appears innocuous at first glance, as if the existing data is simply being reformatted into a structure that's easier for the next step to digest. Only after examining every detail of each conversion did we discover that signature verification subtly transforms each Transaction into a RuntimeTransaction. This conversion accesses the global state to resolve lookup tables.

Agave's design has a compelling strength—it is very easy to write new code, since calling RuntimeTransaction::try_from(transaction, bank) implicitly gathers whatever data is needed from the global state. Lookup tables are resolved automatically without the programmer even realizing that it was necessary.

When designing Sig, we prioritize readability over writability. This involves a higher upfront cost, but it pays off in the long run by improving maintainability. To make the code as readable as possible, we surface critical operations at the top level with a clear sequence of steps. replayActiveSlots begins by calling prepareSlot, whose sole job is to collect all the data required for the slot. Lookup-table resolution is performed explicitly in prepareSlot via resolveBlock.

Transaction Processor

A Solana transaction is an authorized unit of work that combines one or more onchain operations into a single, all-or-nothing action. Each transaction includes a list of instructions to execute, the accounts they interact with, and the signatures required to authorize those actions.

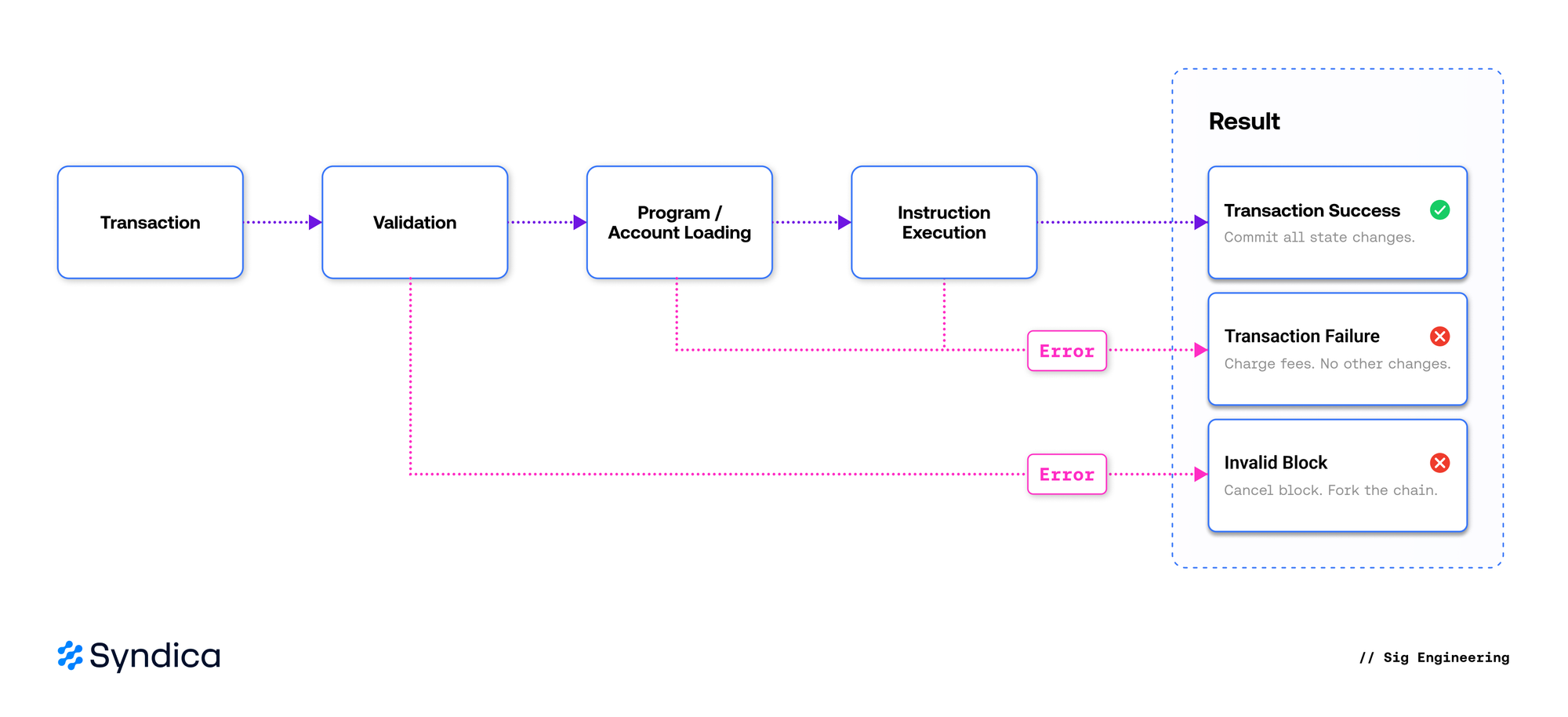

The transaction processor is responsible for transforming transactions into account state changes. While simple to describe, implementing a processor that conforms to Solana’s specification is challenging: both explicit and implicit behaviors must be reproduced with absolute precision, as any deviation in effects will break consensus. At a high level, each transaction passes through three key stages: validation, program and account loading, and instruction execution.

Validation ensures that the transaction is well-formed, the signatures are correct, it has not been previously executed, and the fee payer is valid and has sufficient funds to cover the transaction cost. During replay, if a transaction fails validation, the block is marked as invalid because a leader should never include a transaction in a block that cannot be charged fees.

Program and account loading ensures that all programs and accounts requested by the transaction instructions are available, and that the total size of loaded accounts does not exceed the maximum specified by the compute budget. Programs undergo additional checks to ensure that their bytecode is valid and they can be executed safely. Since this is a computationally expensive operation, validated programs are stored in a cache to prevent duplication of work.

Once the transaction is validated and its programs and accounts are loaded successfully, execution simply involves calling the instruction processor for each instruction. If all instructions succeed, all resulting account state changes will be committed. If any instruction fails, the transaction fails immediately, and the only resulting state change is the charge to the fee payer.

Sig uses a single data type, TransactionContext, to simplify state management throughout instruction execution. It contains the information required to process each instruction, enforces resource constraints, tracks intermediary state, and records the final result and metadata. While this sounds like a lot, it is specified in under 300 lines of code and provides the instruction processor with a clean API for data access and mutation. The resulting instruction execution can be found here, and is closely approximated by the following pseudocode.

var transaction_context = TransactionContext.init(...);

var transaction_error = null;

for (transaction.instructions) |instruction| {

executeInstruction(transaction_context, instruction) catch |err| {

transaction_error = TransactionError{ .InstructionError = err };

break;

};

}

Although implementations have some flexibility in their internal design, conformance requires careful attention to error sequencing. Reordering fallible operations can cause a transaction to fail at a different point and produce a different error. While this doesn’t necessarily affect consensus, since account state often remains unchanged, it can lead to differences in RPC outputs and ledger metadata. For users and developers, that means confusing discrepancies in transaction status and error reporting across validator implementations. Matching Agave’s error sequencing strengthens confidence in behavioral equivalence and aligns with the approach used by existing conformance frameworks.

Instruction Processor

A Solana instruction is simply a request to invoke a program with some input data and a list of accounts it can interact with. The instruction processor is responsible for carrying out this invocation.

Solana makes no assumptions about the form of the program’s input data, allowing programs to choose what it represents. Usually, the input data specifies a command for the target program to execute. For example, the system program expects input data that can be deserialized into a system program instruction.

On the other hand, an instruction’s accounts must be specified in a standard format, indicating whether the account is writable and whether it signed the transaction. This is necessary because the invoked program needs to be aware of which operations are authorized for the provided accounts. For example, when executing a transfer, the system program requires that the sender is both a signer and writable.

pub const Instruction = struct {

program: Pubkey, // Target program address

data: []const u8, // Arbitrary program input

accounts: []const struct { // Accounts with permission metadata

address: Pubkey,

is_signer: bool,

is_writable: bool

},

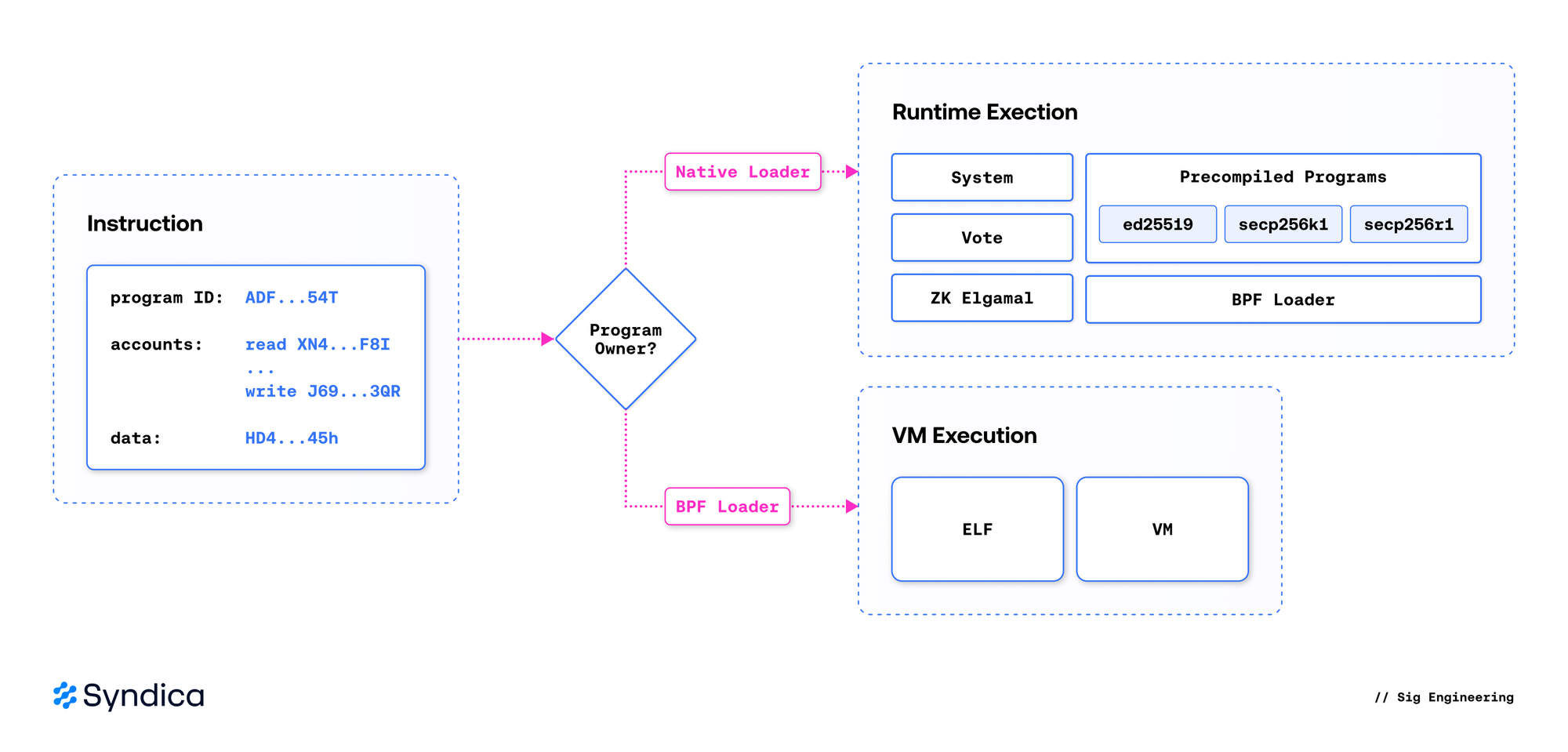

};Broadly speaking, there are two program types: native and sBPF. Native programs are special programs implemented within the validator and invoked directly by the runtime, whereas sBPF (onchain) programs are user-defined and consist of arbitrary bytecode that runs inside the sBPF virtual machine.

Importantly, every program (whether sBPF or native) has an associated onchain account that must be loaded and made available to the instruction processor. To invoke a program, the instruction processor first determines its type by inspecting the program account’s owner: native program accounts are owned by the native loader, while sBPF program accounts are owned by one of the BPF Loader programs.

When the target is a native program, the instruction processor directly invokes the program’s entrypoint. When the target is an sBPF program, the processor instead loads and executes the target program’s bytecode within a provisioned sBPF virtual machine.

Sig has leveraged the fact that Native programs are defined within the validator by invoking them directly, instead of through the sBPF VM as done in Agave. While Agave provides a unified approach to program execution, it comes at the cost of setting up an additional sBPF VM for every program invocation. From our experience, treating Native and sBPF program invocation distinctly also makes program execution easier to understand. The runtime executes Native programs directly, and the sBPF VM only executes sBPF programs.

BPF Loaders

BPF Loaders play a pivotal role in Solana, as they define the mechanisms by which users interact with onchain programs. A BPF Loader is a native program that is responsible for managing sBPF programs. By invoking a BPF Loader, a user can deploy or upgrade an sBPF program.

BPF Loader Versions

As the network evolves, Solana introduces new BPF Loader versions that implement updated deployment rules. Eventually, older BPF Loaders are deprecated and disabled, but the programs they deployed remain invocable.

Currently, there are four native BPF Loader programs. Versions one and two are deprecated and only support program invocation. Version three—commonly referred to as the BPF Upgradeable Loader—is currently active, while version four has been defined but not yet released.

BPF Upgradeable Loader

As the name suggests, the BPF Upgradeable Loader was introduced to enable upgrades to onchain programs after their initial deployment. This provides developers with the flexibility to fix bugs or introduce new features without needing to deploy a separate program and migrate their users to the new program. Since it is the currently active loader, we take a closer look at its mechanics.

The Upgradeable Loader supports permissioned creation, deployment, modification, and closing of onchain programs. This is facilitated through 10 instructions, which are each guarded by a designated program authority.

Program Authority

The program authority is an address specified in each program’s metadata account to identify the program’s owner. Any instruction that modifies a program via the Upgradeable Loader must include the authority address and its signature.

The authority can transfer its ownership to another address at any point using the Loader’s set_authority instruction. This includes assigning an empty authority address. Such a transfer serves as the final mutation for a program because, without an authority, no one can make modifications, effectively freezing the program and rendering it immutable.

Immutable program accounts remain callable through Solana instructions. The act of nullifying the authority provides callers of the program assurance that it will not change unexpectedly before being invoked—a useful property to have, especially for SPL Tokens, which handle balance transfers.

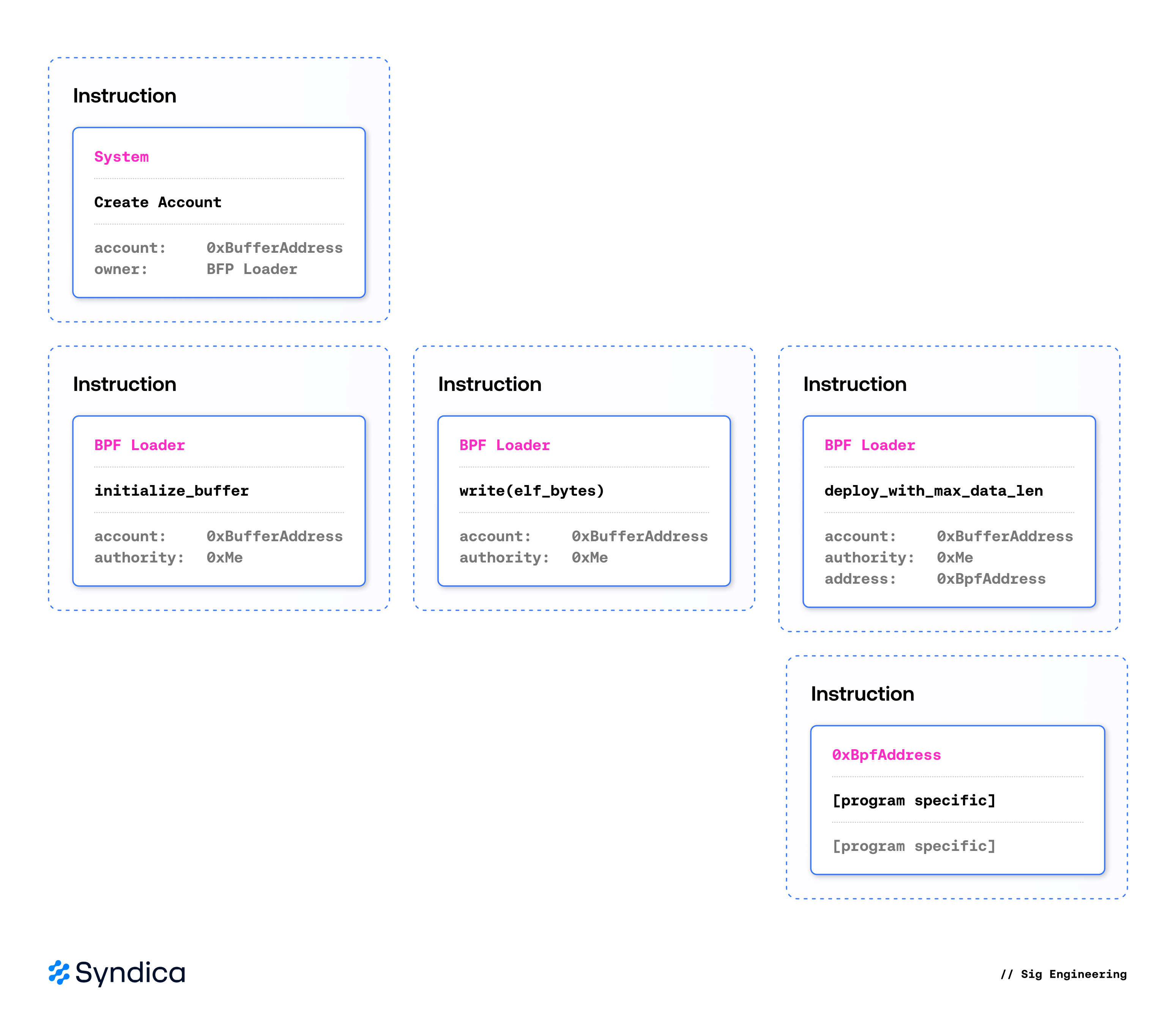

Deployment

sBPF programs must be deployed in the same way that any data gets onchain, by packaging them into transactions. Solana transactions are limited to 1232 bytes, which may be too small to contain an entire sBPF program. To address this, a program’s bytecode is written through possibly multiple transactions, into an onchain buffer account before being deployed.

A buffer account is created with an initialize_buffer instruction to the Upgradeable Loader. This instruction specifies the program authority, restricting who may modify the buffer account in the future. It is then populated with write (and optionally extend_program) instructions until the full sBPF program is loaded onchain.

Once all code has been written, a call to the Loader’s deploy_with_max_data_len instruction makes the program available for execution. It takes the buffer account’s data (now containing the authority and bytecode), validates it, and copies it to the desired program account. At the next slot, the deployed program can be executed via an instruction to the program account.

Upgrading

After deployment, a program can be upgraded and redeployed using the Loader’s upgrade instruction. This feature is what gives the Upgradeable Loader its name—the ability to change a BPF program without requiring a new deployment at a different address. The upgrade instruction behaves similarly to the deploy instruction, taking in a loaded buffer account and then updating the program’s account to hold the new sBPF bytecode.

Administration

As mentioned, if the user wishes to prevent future upgrades to a deployed program, its authority can be set to null. Alternatively, the program can be deactivated using the close Loader instruction, preventing it from being executable from the next slot onwards. In the future, some BPF programs may wish to move from the Upgradeable Loader to the V4 Loader. Once Loader V4 is available, the migrate instruction can be issued to the Upgradeable Loader to transfer an existing program account, redeploying it with the new loader in the process.

Regardless of which Loader an sBPF program is deployed by, they can all be executed via a Solana instruction. Such execution must simulate a real-world machine running sBPF bytecode, with its own memory, I/O, and ability to interact with the runtime. This is performed by the sBPF virtual machine.

sBPF Virtual Machine

The sBPF virtual machine is the part of the runtime that executes every onchain program. A virtual machine is software that simulates an entire computer: it reads a program, interprets its instructions, and produces a result—just like a physical CPU. Every computer supports an instruction set, which is the collection of operations it can perform. On Solana, the instruction set is sBPF, a variant of eBPF created specifically for the chain.

We implemented an sBPF virtual machine from scratch. It consists of the following core components:

- Memory Map: Translates virtual addresses used by the sBPF program into native addresses. When the sBPF environment is initialized, it allocates regions for the stack, heap, account data, and program memory.

- Interpreter: A state machine that executes sBPF instructions. These instructions range from basic arithmetic operations to syscalls and memory accesses.

- System Calls: A predefined set of native functions callable from sBPF programs. Expensive operations such as hashing, cryptographic primitives, and bulk memory operations are delegated to syscalls for performance and correctness. Cross-Program Invocation (CPI) is also a type of syscall, which will be covered in the next chapter.

Memory Map

The memory map translates the addresses used by the sBPF program into real hardware addresses of memory allocated on the host machine. You can find the implementation here. Internally, the memory map is a tagged union because a memory map can be either aligned or unaligned:

pub const MemoryMap = union(enum) {

aligned: AlignedMemoryMap,

unaligned: UnalignedMemoryMap,

};In sBPF, certain virtual addresses have a unique meaning. For example, 0x200000000 is the address used to represent the stack memory, while 0x300000000 represents the start of the heap memory. These two addresses are 4 GiB apart from one another, and since we don’t want to allocate gigabytes of memory to represent the relatively small stack and heap sections, we need to split the mapping into chunks.

The memory map is abstracted into Regions, which are spans of memory on the host machine mapped into the virtual address space.

pub const Region = struct {

host_memory: HostMemory,

vm_addr_start: u64,

vm_gap_shift: std.math.Log2Int(u64),

vm_addr_end: u64,

};

The host_memory represents the memory region on the host machine that backs the VM’s region. vm_addr_start and vm_addr_end represent the bounds of the virtual address space that the region represents. For example, the stack is represented as a region where vm_addr_start is 0x200000000 and vm_addr_end is the start address plus the length of the stack.

Typically, input data for an sBPF program is copied into the memory regions created for the VM. However, the sBPF virtual machine has a feature known as data direct mapping, which is a performance optimization that allows the program being executed by the VM to directly access account data as it already exists on the host, without needing to copy it. This requires a separate region for each account to map its data into the virtual address space. This is where a fundamental limitation of the aligned memory map becomes a problem, necessitating unaligned mapping.

The aligned memory map looks at the top 32 bits of the address to determine which memory map region the virtual memory lies in. Let’s say we have a virtual address 0x2000001234, and we need to determine which region it belongs to. By shifting the address to the right by 32 bits (0x2000001234 >> 32), we get 2, which is the region number that represents the stack. We can use this number to directly index into our list of regions and get our result.

For context, the first region is the data region, which stores data to be used by the program. An inherent limitation of this design is that the virtual addresses represented by each Region must be 4 GiB apart from one another. Otherwise, they would result in the same index after shifting, and we wouldn’t be able to distinguish between them.

This is where the unaligned memory map comes into play. Instead of just looking at the top 32 bits of the address to determine the index, it stores the regions in a sorted list, ranked by the virtual address they represent. Then, when it is time to look up the region for a particular virtual address, the memory map performs a binary search in this list. This removes the spacing limitation imposed by the aligned map, but the downside is that it increases the time complexity of finding a region from O(1) to O(log(n)) for n regions.

The interface to the memory map is quite simple:

/// Retrieves a value of type `T` from a given virtual address

pub fn load(self: MemoryMap, comptime T: type, vm_addr: u64) !T

/// Writes a value of type `T` to a given virtual address

pub fn store(self: MemoryMap, comptime T: type, vm_addr: u64, value: T) !void

These functions handle translating the addresses, checking alignment, and access permissions.

Interpreter

The interpreter is a small and deterministic state machine. Each step involves fetching the next instruction, decoding it, and executing its effects on the state. The heart of the implementation lies in three functions:

stepexecutes a single instruction.runcallsstepin a loop until the program halts or errors.dispatchSyscallhandles calls to the native functions.

step fetches and executes the instruction at the current program counter (pc). Each sBPF instruction is 8 bytes long and stored at a specific offset within the ELF binary. The program counter is a register that keeps track of the interpreter's current instruction. Usually, step increments the program counter by one after each instruction to move on to the next instruction. Some instructions, like jump and branch, update the program counter to an arbitrary value.

Instructions

sBPF instructions are 8 bytes long and contain five fields that Sig represents with a packed struct:

pub const Instruction = packed struct(u64) {

opcode: OpCode,

dst: Register,

src: Register,

off: i16,

imm: u32,

};

The opcode determines what operation to perform, dst and src specify registers to fetch data from, imm is an immediate (a value that is hard-coded into the program and the instruction encoding, allowing it to be used directly instead of fetching it from a register), and off is the offset used by jump and branch instructions to tell the interpreter how far away to jump.

Here is a simplified example of how arithmetic instructions could be implemented in the interpreter:

// Retrieve the current program counter.

const pc = registers.get(.pc);

// Fetch the instruction from memory.

const inst = instructions[pc];

// Fetch the data from the registers.

const lhs = registers.get(inst.dst);

const rhs = registers.get(inst.src);

// Perform the calculation.

const result = switch (inst.opcode) {

.add => lhs +% rhs,

.sub => lhs -% rhs,

.mul => lhs *% rhs,

.div => try divTrunc(lhs, rhs),

...

};

// Store the result back in the registers.

registers.store(inst.dst, result);

In the actual implementation, there are plenty of quirks to the process, which often require special handling, but it all boils down to this. We fetch data from the registers, which are part of the state, perform a computation, and store the data back into the very same registers.

Notice that we retrieve the lhs input from the same register where we’ll store the result later. This is because sBPF is a two-address instruction set architecture. The instructions don’t have room to include a third register, so most operations work by performing computation on a value already stored inside the destination register. This can reduce the size of the instructions, but the downside is that certain patterns require more instructions to represent, which may take longer to execute.

Dispatching System Calls

In sBPF, system calls (syscalls) are functions that implement a sensitive or computationally intensive task. Consider SHA-256 hashing or elliptic curve cryptography primitives. These operations can greatly benefit from being optimized to run directly on the native hardware used by the validator, which can be achieved by invoking them via syscalls.

To instruct the interpreter to run a specific syscall, the sBPF program uses the syscall instruction. This is an instruction with the opcode set to syscall. It identifies the syscall by placing the Murmur3 hash of the syscall's name in the immediate field. Our interpreter then looks it up in a registry that stores a mapping between these hashes and the function pointers that implement the syscall.

Once we find the syscall’s function pointer, we only need to call it with the provided context. The syscall implementation then fetches data from the registers, performs the required computation, and returns the results to the program by updating these registers with the new data.

Future Improvements

Our concern when implementing the sBPF VM was correctness rather than performance. The current design performs well, as it compiles down to a small jump table, due to the large number of shared instruction implementations, like the arithmetic example given earlier.

In the future, performance can be significantly improved for larger programs by utilizing just-in-time (JIT) compilation. With this method, a lightweight compiler scans over the instructions in the program just before execution and converts them into machine code instructions that can be executed natively on the validator at a much higher speed. The tradeoff is that the pre-compilation step also takes time, potentially making the entire process slower for smaller programs. JIT compilation is a widely studied field with many interesting approaches and nuances. In the future, Sig will likely use a copy-and-patch JIT approach.

Cross Program Invocation

As discussed earlier, transactions contain instructions that describe program invocations executed by the instruction processor. Solana extends this model by allowing programs to invoke other programs through a process known as Cross-Program Invocation (CPI). This mechanism enables programs to interact and compose with one another, allowing complex behavior to emerge from smaller, modular components.

Essential to CPI is the instruction stack—a structure that tracks the currently executing program, allowing CPI calls to return the results to their calling context. An instruction specified within a transaction begins its execution by being pushed onto an empty stack. Afterward, the instruction processor reads it from the stack and invokes its target program. When a CPI occurs, a new instruction is pushed onto the stack; the instruction processor recognizes this and immediately begins executing the new instruction. Once a program runs to completion, its result is recorded, and its associated instruction is popped off the stack.

A crucial component of CPI is the management of account privileges—specifically, preventing privilege escalation between program invocations. When a new instruction is pushed onto the stack, the runtime verifies that its associated account permissions are compatible with those specified by the topmost instruction. This ensures that a program invoked via CPI can never perform actions that exceed the privileges granted by its calling context.

This process is straightforward for native programs, as they are implemented directly within the validator runtime. In Sig, native programs perform CPI by calling executeNativeCpiInstruction with the desired instruction. However, things become more complex for sBPF programs, as both the instruction and its result must be translated between the runtime and the virtual machine executing the current program. sBPF programs trigger CPI through one of two syscalls—sol_invoke_signed_rust or sol_invoke_signed_c—which take a VM representation of an instruction, convert it into the runtime’s internal format, verify privileges, and push it onto the instruction stack for execution.

Typically, sBPF programs are written in Rust before being compiled into bytecode. But given that sBPF is a standardized bytecode format, any source language that targets it also functions for writing BPF programs. To accommodate ABIs outside of Rust-compiled programs, a separate syscall was established to use the C ABI, providing a universal and stable memory layout for the VM data types.

In Agave, there are multiple translation functions to read from each ABI into a standard type; however, Zig comptime allows Sig to write it once and generalize only the data type as opposed to all of the translation logic. This limits the chance of the implementations getting out of sync and untested errors manifesting in one of them.

ZK SDK

The zksdk module implements the zk-elgamal-proof native program, which verifies zero-knowledge proofs embedded in account data. These are among the most compute-intensive operations executed on-chain, some costing hundreds of thousands of compute units, so performance is critical.

Our implementation is several times faster than Agave's and roughly on par with Firedancer's. The performance gap comes from three core design differences:

- Heavily SIMD-optimized Edwards25519 / Ristretto255

- Zero heap allocations

- More optimal multi-scalar-multiplication (MSM) ordering

Heavily SIMD-Optimized Edwards25519 / Ristretto255

We heavily optimized our Edwards25519 / Ristretto255 to take advantage of SIMD operations on any architecture. We also hand-crafted a custom implementation to optimize further for architectures supporting x86-64 AVX512-IFMA.

The portable SIMD implementation uses Zig's @Vector type, which compiles to optimal AVX2 instructions on x86-64 and near-optimal NEON instructions on ARM. The beauty of this implementation is that it is cross-platform, leaving it up to the compiler to emit whatever SIMD instructions are available on the target.

The x86-64 AVX512-IFMA implementation uses the vpmadd52l/vpmadd52h fused multiply-add instructions. These instructions operate on 52-bit limbs, matching the common 5x52-bit representation of elements in the Edwards25519 field (2^255 - 19).

The result is a substantial speedup in proof verification, especially for larger batch operations like RangeProof256, which requires hundreds of point multiplications.

Zero Heap Allocations

All proofs in the ZK SDK have known, fixed upper bounds on memory usage. Our implementation uses only stack memory with no dynamic allocation at runtime. This is made easy with Zig's lack of implicit heap allocations and powerful generics. For example, the RangeProof instruction is a single implementation parameterized by the bit size of the integer it encodes.

Optimal Multi-Scalar-Multiplication (MSM) Ordering

For the sigma-proofs, we reorder the final MSM so that the final output is multiplied by the expected value, allowing us to simply check if the output is the identity point. The difference between the Ristretto comparison, which requires a couple of multiplications, and a single amortized multiplication inside the batch isn't as impactful as the other improvements, but it does save a couple of microseconds off the verification time.

Benchmarks

Here are benchmarks comparing Sig’s performance to Agave and Firedancer. The measurements were taken on a Zen 5, Ryzen 5 9600X, which allows it to take advantage of the IFMA optimization as well as full-lane AVX512 that comes with Zen 5. The benchmarks can be reproduced with this script.

| Agave | Firedancer | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|

pubkey_validation |

40 us | 21 us | 17 us |

zero_ciphertext |

70 us | 38 us | 32 us |

percentage_with_cap |

74 us | 48 us | 43 us |

range_proof_u64 |

1.45 ms | 529 us | 436 us |

range_proof_u256 |

4.92 ms | 1.8 ms | 802 us |

Conformance

Conformance testing plays a crucial role in ensuring correctness in a multi-validator network. As discussed earlier, any divergence in account state between validator implementations will lead to a breakdown of consensus. As alternative implementations gain stake, such divergences can cause network slowdowns—or even a complete halt.

It is therefore imperative that new validator implementations are thoroughly tested for equivalence before they begin to accrue significant stake. One simple approach is to run new validators with a small amount of stake and confirm that they remain in agreement with the cluster. While this should certainly be part of the testing process on the path to wider stake adoption, it is insufficient. There is no guarantee that past transactions have effectively explored the full state space—in fact, this is extremely unlikely.

A more robust approach is to build and maintain a corpus of inputs that target specific regions of the validator and compare the outputs produced by running these inputs across different implementations. Breaking the problem down in this way makes it easier to understand and improve coverage, debug discrepancies, and take an incremental approach to conformance testing—gradually expanding the scope of targeted regions until the entire runtime is encompassed. Corpus inputs can be hand-crafted or generated programmatically by fuzzing engines designed to produce inputs that trigger execution paths not yet covered by the existing corpus.

Building and maintaining such a testing framework is a significant task. Efforts from the Firedancer team in developing and open-sourcing solfuzz-agave, protosol, test-vectors, and solana-conformance have laid the groundwork for Sig’s conformance-first approach to development.

solfuzz-agave implements API bindings (referred to as test harnesses) for Agave components, protosol defines the input and output schemas for these harnesses, test-vectors contains a large corpus of test cases, and finally, solana-conformance ties everything together into a simple tool for comparing the behavior of different validator implementations.

| Harness | Detail | Public Corpus Size |

|---|---|---|

elf_loader |

ELF parsing | 198 |

vm_interp |

sBPF program execution | 108,811 |

vm_syscalls |

sBPF syscall execution | 4,563 |

instr_execute |

Instruction execution | 21,619 |

txn_execute |

Transaction execution | 5,624 |

Sig now runs solana-conformance with the above harnesses as part of its continuous integration (CI) pipeline, ensuring ongoing compliance with Solana’s reference implementation. In collaboration with Asymmetric Research, we have also expanded our testing beyond the test-vectors repository. As new issues arise, we contribute the corresponding failing test cases to the public corpus, helping to improve coverage for the entire ecosystem.

Conclusion

Sig makes Solana more resilient by adding a third, fully conformant runtime built from scratch. That’s the baseline: correctness first. We’re grateful the community laid the groundwork for conformance testing, and we’ll keep contributing back to the public corpus.

Now that the foundation is in place, we’re shifting focus to performance. There’s plenty of low-hanging fruit: zero-copy account reads, allocation-free execution, and JIT compilation. Follow along on Twitter to hear about this and more as we push our next round of updates.

Sig exists to make Solana clearer, faster, and more resilient—and this is just the beginning. If you're passionate about clean code, low-level optimizations, or testing assumptions until they break, join us.